What I’m reading: another fine novel from the doyen of gay English authors

Alan Hollinghurst: OUR EVENINGS

I approach a Hollinghurst novel, especially one as bulky as this, with some apprehension, since he often seems to be channelling Henry James, with drawn-out descriptions and a snail’s pace. Pleased to report that these are not issues with Our Evenings, an autobiographical study of a mixed-race British actor, David Win, the product of an expatriate Englishwoman’s brief affair with a Burmese officer. His mother settles into a lesbian marriage, which gives David as much security to grow up in as any other boy, although his skin colour always sets him apart right up to the book’s ending in the era of Covid lockdowns.

The story begins with his schooldays on a private scholarship to a boarding school on the South Downs. Giles Hadlow, his benefactor’s son, is a fellow boarder and casts a shadow over David’s life that lasts beyond school. David’s natural gift for comedy makes him popular, and he enjoys the sexual favours of several other boys. As we know, many boys grow out of schoolboy homosexuality. David is one of those who doesn’t, and as his acting skills take him without too many setbacks into a long and multi-faceted career in theatre and television, there are flings and love affairs, although not until middle age does he find a love that endures. Giles Hadlow, a Minister in the Cameron administration, reappears, as do some other Old Boys from their schooldays.

Hollinghurst is, I think, unchallenged as the doyen of British gay authors, and Our Evenings (odd title) plays out against the societal changes in gay life pre- and post-Liberation, through HIV/Aids to where we are now, with same-sex marriage and parenting. This is a big book with a big cast of mostly likeable characters, all splendidly rounded, and an engaging storyline, which gets richer with each passing decade. A few critics have hailed this as Alan’s best novel, but for me only A Line of Beauty came close to the outstanding level of his debut, The Swimming-Pool Library and that may owe something to the superb TV adaptation. Our Evenings is good, very good, but not quite in the pantheon of supreme gay fiction.

David at the movies: the birth of Richard Burton

Mr Burton

An atmospheric version of the early life of Richard Burton, the miner’s son who became one of the greatest stage and screen actors of his time and married Elizabeth Taylor, not once but twice.

The Mr Burton in the title is not the star but the village schoolteacher Philip Burton, who wrote radio plays as a sideline and coached young Richard Jenkins in the art of acting; needing a stage name, Young Jenkins became Richard Burton. Toby Jones is very much the “flavour of the year” and in perfect pitch here as the man who saw the boy Richard’s potential and nurtured his modest talent into the strato-sphere. Lesley Manville has a fruity role as Philip’s landlady, who is so motherly that they both call her “Ma”.

The script tentatively hints at homosexuality – why did Philip devote so much of his life to this particular schoolboy? – but possibly for want of evidence this issue fizzles out.

Harry Lawtey delivers a believable portrait of young Richard, the uncouth son of a hard-drinking coalminer who almost accidentally turns out to have the makings of an actor. Getting him to “talk proper” gives the movie some humour and is, of course, the core of what made Richard a star. Lawtey is good in the transitional stages but he doesn’t get the mature Richard’s glorious resonance quite right; it comes across as a bit of a parody. But the tone of the movie is fine, with none of the hyperbole that usually messes up Hollywood biopics.

By chance I watched an early Burton movie on TV last week, The Robe, the Biblical epic that was famously the first movie in CinemaScope. We hear the voice of Jesus but never see his face, relying on the reactions of the other characters, including (oh dear) Victor Mature, one of the prime contenders for the All-Time Worst Actor award. The best thing in the movie is Jay Alexander whose shrieking Emporer Caligula recalls Kenneth Williams’s Captain Ahab in Round the Horne. Our Richard doesn’t look too comfortable in a leather miniskirt tunic but That Voice gives his Marcellus a kind of magic. That Voice made him the best-ever King Arthur in the Broadway cast of Camelot: aping Rex Harrison’s approach to talking in a musical voice when you can’t sing was never better than Burton’s Arthur.

But he could be a klutzy boy on screen (and on stage too: they say his Private Lives with la Taylor was beyond travesty). In some of the movies he made with Liz you can almost see him sneering at the script (“Sorry, people, I know this is crap but we needed the money”) whereas she always gave a good performance even in bad movies, which is the hallmark of a true professional. Of course, at their best – in, say, The Taming of the Shrew and (sublimely) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, — they were the crème de la crème.

![]() One of these days I must post on here the naughty details of the call I listened in on between Liz (at the Dorchester) and Richard (in Yugoslavia) back in my career as a telephonist at the Continental telephone exchange in London. Spicy!

One of these days I must post on here the naughty details of the call I listened in on between Liz (at the Dorchester) and Richard (in Yugoslavia) back in my career as a telephonist at the Continental telephone exchange in London. Spicy!

Mr. Burton can be seen for free on BBC iPlayer

What I’m reading: Whodunit loved by millions. Not by me.

RICHARD OSMAN: The Man Who Died Twice

Green with envy at Richard Osman’s runaway success, I was determined not to like The Man Who Died Twice, but I was quickly won over by his style, which is as light and likeable as his appearances on Pointless and other television shows. I didn’t read The Thursday Murder Club but I enjoyed the movie, which had much of the geniality and whimsicality of the Peter Ustinov Agatha Christie movies.

Elizabeth, the Helen Mirren character, is again at the heart of the story. Decades ago, early in her Secret Service career, she helped to fake the death of a man she later married. Now her ex-husband reappears, on the run with twenty million pounds worth of a mobster’s diamonds. When he turns up dead again, she and her three chums from the retirement home aren’t sure whether he’s actually been murdered or faked another death in order to start a third new life.

Getting involved with drug-dealing gangsters is dangerous territory for Elizabeth, Joyce, Ibrahim and Ron. One of them is badly beaten, and they all have a few close calls.

To fully enjoy this story, you have to take the four pensioners to heart, and whilst I did initially warm to them, 420 pages of their biting banter wore me down. I never went off Peter Ustinov’s Poirot, but I did find David Suchet’s wearisome. Joan Hickson’s Marple never lost her charm, whereas Geraldine McEwan’s and Julia McKenzie’s I never took to, much as I adored both actresses in other roles they played. Of the four leads in The Thursday Murder Club movie, Celia Imrie’s Joyce was the one I liked most, although on the page in The Man Who Died Twice she got on my nerves quicker than any of the others; Ron (Pierce Brosnan) is the only one I didn’t find a pain in the bum after a few hundred pages. And I totally lost interest in whodunit.

Clearly the nation (the nations, plural) have taken this series to their heart. I, clearly, have not, but I sincerely congratulate Mr Osman on coming up with a winning formula. I’m unlikely to read him again, but I’ll almost certainly watch all the movies.

David at the Movies: the Lady is a Tramp

DOWNTON ABBEY: THE GRAND FINALE

If you can remember the very first episode of the first series, Lady Mary Grantham (Michelle Dockery) was caught in a compromising situation with a ship that (literally) passed in the night. Well, she’s up to her old tricks in the latest– and final, for now – episode. Newly divorced, she is shunned by London society and shocks the audience (you and me) by having a drunken one-night stand which is not likely to end at the altar. (Things are a bit different now with divorcees on the throne and throughout society, high and low. There are Ladies today who are seen as tramps, but trampiness is now more of an accolade than an obstacle.)

Restoring Mary’s position in London and the country seat is the central plank of the story, together with a general handing over of the reins. Daisy is taking over as cook as Mrs Patmore retires. Andy the valet is the new butler, with Carson finding a new role in the local community and Barrow enjoying life as movie-star Guy Dexter’s PA/lover. And his lordship (Hugh Bonneville) is trying to let go the running of Downton Abbey. If she stays unattached, Mary will be able to replicate Maggie Smith’s salty dowager duchess about forty-five years from now.

As in the previous movies, all our favourites are back. Everybody gets a piece of the action. Dame Maggie and Dan Stevens and Mary’s dead sister are all shoe-horned into a flashback. Noel Coward has a (slightly too large) guest role, brilliantly captured by Arty Froushan.

The Upstairs and Downstairs occupants of Downton are people we have taken to our hearts, and Julian Fellowes’s screenplay once again does them all proud. Despite the ominous title and all the bowings out, I think we can hope that there will be Downton: the Return in a few years; opening the house to day visitors is an obvious next step. As a superior soap-opera Downton is more splendid than Upstairs, Downstairs which clearly inspired it and very close to the perfection of Jewel in the Crown and Brideshead Revisited, the twin pinnacles of this kind of gem-quality entertainment. High praise to everybody involved.

What I’m reading: Carry On Bonking!

Tom Cutler: SLAP AND TICKLE

I wasn’t going to bother with this when a friend gave it to me. The title, the cover, it all looked a bit puerile and crass. Well, yes, it is puerile and crass, but it’s at least as much fun as a Carry-On movie, with lashings of schoolboy smutty humour. For example, the Prince Regent is described as “a sort of proxy – not to say poxy – monarch.” The dress code and forms of address in BDSM sessions mean it “sounds like the Church of England”.

Some of the historical snippets we’ve heard before but it’s good to be reminded of them. Lord Wolfenden referred to homosexuals and prostitutes as “Huntleys and Palmers” during the gathering of data for his Report in the late 1950s. Mary Whitehouse was “a Christian social activist known for her prominent opposition to everything, and her pursed lips.”

Tom Cutler adds some droll details to sexual history. Professor Kinsley filmed his volunteers having sex in his attic; Mrs Kingsley provided clean towels and milk and biscuits. Stephen Ward had been a carpet salesman before he turned osteopath and high-society pimp. After the Profumo Affair Mandy Rice-Davies described her life as “one slow descent into respectability.” Sploshing was a new fetish to me, involving baked beans or custard or other “sploshy” foodstuffs. Do you eat them afterwards?

Words of wisdom that you may not have seen in quotation compendiums. James Joyce: “It is wonderful to fuck a farting woman.” Graham Greene (no less) praised the French classic Histoire d’O: “a pornographic book well-written and without a trace of obscenity.” Tom Cutler includes a few pages from four other porn classics, including Fanny Hill, my personal favourite which is like a bawdy sequel to Tom Jones – I bought my copy from a bookshop on the Via Veneto in Rome in 1969.

This is an enjoyable romp through many (most) aspects of Sex. I’ll close with what seems to me a great truth Mr Cutler quotes: “Somebody once said that the big difference between sex for money and sex for free is that sex for money usually costs less.” And a 1997 British Medical Journal study of men aged 45-49 found that those who had little or no sex were twice as likely to be dead ten years later than those who had two or more orgasms a week. Men in that age group may need to take themselves in hand.

What I’m reading: Daft title but it tugs on your heartstrings

ISABEL ALLENDE: The Wind Knows My Name

In 1938 Samuel Adler, aged five, escapes the new Nazi regime in Austria with other Jewish children on the Kindertransport. He will lose his entire family to the Holocaust, but his prodigious talent as a violinist will see him forge a lifelong career in England and, later, America. In the 2020s, in California during the Covid pandemic, seven-year-old Anita Diaz, a refugee from war-torn El Salvador, is separated from her mother by the Trump administration’s harsh policy towards illegal migrants. Like Samuel decades earlier, she drifts from one form of fostering to another while Selena, a Latina lawyer with a refugee background, tries to find Anita a permanent home and track down her mother.

Family ties and tragedies have been Isabel Allende’s stock-in-trade since her 1980s debut with The House of the Spirits, which was richly steeped in magic realism. She is a master storyteller and her novels are always good and occasionally outstanding. I would rate The Wind Knows My Name – really that title is a bit daft – as one of her good rather than great efforts. The characters are vividly drawn, but the plot is contrived and the writing is somewhat uneven compared to her greatest novels, which may be the author’s fault or her editor’s or perhaps her translator’s. Some chapters narrated by Anita as if talking to her dead sister, I found cloying and clumsy. But, slightly flawed, this is a rewarding read and, in several parts, it tugs hard on your heartstrings.

What I’m reading: George Clooney should play Gabriel Allon!

DANIEL SILVA: A Death in Cornwall

A subset within the main series of Gabriel Allon adventures, this is a sequel to the previous year’s The Collector. Having retired (conveniently, given current events in Israel/Palestine) from his role as head of Israel’s secret service, Gabriel is concentrating on his other career as an art restorer in Venice. Lured by an old friend to investigate a murdered art historian in Cornwall, he is soon caught up again in the shameful saga of the trade in Old (and New) Masters, especially those stolen by the Nazi hierarchy in World War Two from Jewish owners deported to the death camps.

The trail leads to Corsica and Monaco and the so-called Freeport in Geneva (which really exists) where paintings are stored and traded, along with other assets and property transactions and cash on a tax-evading basis, by some of the world’s richest people, including heads of state and Russian oligarchs. Silva ties all this in with the pending resignation of a short-lived female prime minister in Downing Street, which certainly gives this tale an extra “bite”.

Here, again, is Daniel Silva in “caper” mode, although with murders and abductions the story is almost as high-tensioned as one of his international terrorism thrillers. Several familiar characters are in the supporting cast. I found myself mentally adapting A Death in Cornwall for the cinema or Netflix, with George Clooney as Allon and Catherine Zeta-Jones as the cat-burglar turned part-time secret agent. It would make a terrific movie, with hefty dollops of the humour and glamour of the 1955 Cary Grant/Grace Kelly To Catch a Thief.

This is Daniel Silva “lite”, but a cracking good story and a real page-turner.

What I’m reading: Western intelligence versus the FSB (KGB)

Charles Cumming: JUDAS 62

My last review was a book I thoroughly disliked. Now here’s one for a book I hugely admire. Judas 62 is a sequel to Box 88 and reintroduces us to Lachlan Kite and Box 88, an ultra-secret espionage agency based in London and operating in parallel to both MI6 and the CIA.

It’s a story in two distinct halves. In 1993 while still at university, Kite accepted a mission to ‘exfiltrate’ a Russian biological weapons scientist who wanted to defect. In 2020 he finds that the FSB, the former Soviet KGB, have put him at Number 62 on their ‘Judas’ list of targeted enemies, a list that included Alexander Litvinenko, who was successfully eliminated (2006), and Sergei Skripal, who with his daughter narrowly survived poisoning in Salisbury (2018).

Kite mounts a ‘sting’ operation in Dubai using the scientist he brought out in 1993 as bait for FSB revenge. This mission, like the defection, requires intricate planning and timing down to the minutest detail. A beautiful double agent plays a key role.

Once again Charles Cumming gives us a spy world somewhere between the different Whitehalls of John Le Carré and Ian Fleming. Lachlan Kite is more George Smiley than James Bond, and the writing feels much closer to the real war between rival intelligence services than the fantasy global threat of Blofeld’s SPECTRE.

Judas 62 is up there in the ‘pantheon’ of spy fiction, an engrossing and thrilling read. There’s a third instalment which I can’t wait to delve into.

What I’m reading: Morocco minus the magic

Dinah Jefferies: NIGHT TRAIN TO MARRAKECH

I hate to write a bad review, but this is one of the most irritating novels I’ve read in a long time. The title grabbed me – a brief visit to Marrakech decades ago left an impression that haunts me still – but the title is fake, a tease: Vicky arrives in the city by train in the opening chapter, but that’s the only rail journey in the 450-page book.

There are too many characters: Vicky, her grandmother and (later in the story) her mother and two aunts; and Bea, a girlfriend whose disappearance is one of the key story elements. Each of the women has a male support role: a boyfriend, a husband, an ex or a potential squeeze. Vicky’s mother has a guilty secret in her past which is over-trailered and a long time coming. Too many characters and not enough plot: Vicky and Bea witness a murder, but there is little mystery attached to the killing.

Dinah Jefferies thanks three editors in the Acknowledgements, but I found the book to be poorly edited. ‘A sofa covered in an ochre linen fabric with big squishy burgundy cushions’ – that ‘squishy’ is execrable. ‘He seemed to be holding on, but there had to be such a horrible mixture of emotions going on inside him’ – it can’t be just me who finds that trite and inadequate. Yves Saint Laurent makes a guest appearance (Vicky dreams of becoming an haute-couture designer), but he isn’t given anything important to say. There is a central thread to the story but the narrative meanders all over the place in order to build up the (negligible) suspense for the Reveal of the Big Secret. If the book was 150 pages shorter the pace would be crisper and the suspense more intense.

I acknowledge my impertinence in dismissing the work of the author and her three editors. This is genre fiction, a ‘Women’s Book’, but here is one male reader who thinks that female readers deserve a better-prepared dish than this. I’m pretty certain Daphne du Maurier would share my low opinion of Night Train to Marrakech. Katie Hutton, my current favourite writer of Romantic Fiction, is so much more readable and fluent. Sorry, Dinah, but as my English teacher used to write on most of my school essays: ‘Can do better. Must do better.’

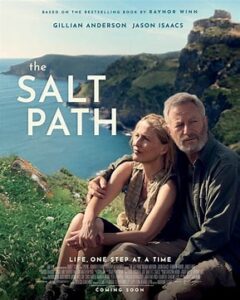

David at the movies: a life-affirming walk along the coast

THE SALT PATH

This is the true story of Gaynor and Moth Winn who walked the cliff-hugging trail from Somerset to Land’s End after Moth received a terminal diagnosis and bailiffs seized their home and everything in it. Living in a flimsy tent on a flimsy budget, they managed to survive a long summer before a renovation project gave them shelter through the winter. Gaynor took up sheep-shearing to boost their funds.

Gillian Anderson, shorn of make-up, gives a powerful raw performance as Gaynor, and Jason Isaacs is on equally fine form. With mostly hand-held cameras the film is fully immersive, making you feel as if you’re rambling in this glorious landscape/seascape with them through weather that is not always glorious.

Like previous road trip movies, this is full of the feel-good factor with moments of the feel-sad factor to break the mood. Anderson and Isaacs set out to milk every ounce of sympathy from you, and you are meant to emerge from this picture feeling that your life has been affirmed as well as theirs. I enjoyed all the ups and downs of the coastal hike.